By Alexa Gola, Associate News & Features Editor

On Oct. 16, freshmen, sophomores and juniors sat down to take the PSAT for what was the class of 2026’s fifth time in high school. In previous years, doing so seemed fairly standard: per state accountability requirements, students were expected to take the SAT in the spring of their junior year, so they took the PSAT each semester to prepare. For juniors, the PSAT also served as an opportunity to qualify for the National Merit Scholarship, which provides $2,500 in scholarships to winners, in addition to a number of corporate scholarships available to finalists and otherwise qualified students. Still, in accordance with the ISBE’s spring 2024 decision regarding the future of state-wide standardized testing contracts, Illinois will require the class of 2026 onwards to take the ACT to graduate.

Consequently, state funding is directed to administering ACT and PreACT tests, rather than the SAT and PSAT. Considering CPS’s present budget crisis, this begs the question of why students will take the PSAT and PreACT in school during the same year. In April 2023, CPS renewed its contract with College Board. This contract stipulates that College Board will provide AP tests in addition to the full SAT Suite of Assessments through the end of the 2025-2026 school year, suggesting that students may continue to take the PSAT using district money through the end of the class of 2026’s time at Payton. Though the contract also nominally includes the SAT as part of the “scope of services” College Board is to provide, Payton’s in-school testing schedule does not currently include the SAT, suggesting that students will not be able to take the exam without paying for it themselves.

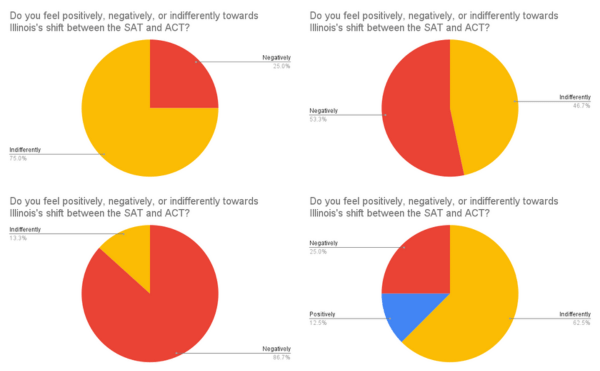

In a survey conducted by the Paw Print, a majority of students said they felt negatively about Illinois’s shift between the SAT and the ACT. One junior said she felt the change was “sudden and unexpected,” and noted that “we are already worried about standardized tests in general.”

Adam O’Mara ‘26 said that students, and specifically juniors, “have spent the past 3 years studying for the SAT with the PSAT. While some students may be able to easily pay for multiple SAT sessions at other schools and/or ACT test prep sessions and resources, this isn’t the case for all students, making the sudden switch inequitable.” He felt that “slowly phasing out the SAT, allowing current juniors to take the SAT, and freshman would do the [PreACT] and later the ACT” would be a better and more equitable alternative.

Another anonymous junior said, “The preparation that I have been doing is all for [the] SAT, so for the graduation requirement to switch without notice is scary to think about. Not only do I have only a few months to study and prepare for the test that can determine my future, but I also have no idea what will be on the test and that, as a student, scares me.” No member of the classes of 2026, 2027 and 2028 indicated that they felt positively about the standardized testing switch.

Freshman John Willow cited the higher cost of taking the PSAT and SAT as his reason for preferring to be required to take the SAT in school. Similarly, an anonymous sophomore said, “As someone coming from a low-income family, I don’t have the means to pay for multiple PSATs and SATs… There’s also National Merit to think about as well. Since Illinois is switching to the ACT, I can’t enter it because it won’t be available to me in 11th grade.”

On the other hand, Hee-Sun Ban ‘27 explained their indifference by saying, “ACTs have always just been easier for me personally, but I’d also like to be able to have the opportunity to try the SAT as well. The shift from SAT to ACT doesn’t really affect me since I already planned to take both at some point. Either would be fine to be required in school.” However, as Willow and other students’ responses illustrated, not everyone has the means to take standardized tests outside of school, highlighting the impact of inequity in the SAT to ACT shift.

“I think the National Merits Scholarship is really important and having the opportunity to take that test is far more important than getting practice on the ACT,” Ban added, explaining their preference for the PSAT/NMSQT. Still, there were also students, often freshmen, who felt that because they would be required to take the ACT in their junior year, they should be taking the PreACT in order to prepare. Sareena Dogar ‘27 believes that students should “take the PreACT” in school because the ACT assessments are “the one(s) required by the state.”

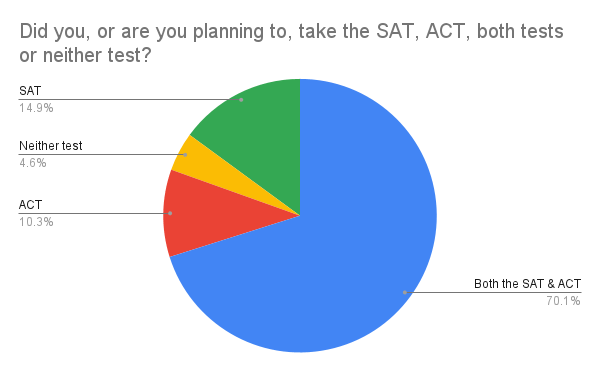

Despite the negative sentiments expressed by a majority of student respondents, it is possible that the impact of the testing change can be minimized. A vast majority of Payton students either have or plan to take both the SAT and the ACT, giving most students an opportunity to take their preferred test, regardless of where state funding goes. Still, not all students welcome the additional stress students associated with studying for a second test, and not all students have the financial means to take a second test. By switching between the SAT and the ACT, the ISBE has amplified inequities that continue to exist within the standardized testing system, potentially harming students that do not have the resources to work around disadvantageous changes.

Leave a comment